Appearance

Grazing Philosophy - Joel Salatin

Joel Salatin offers this thorough description of Adaptive Grazing in his book [[salad-bar-beef]]. In Chapter 18 he writes:

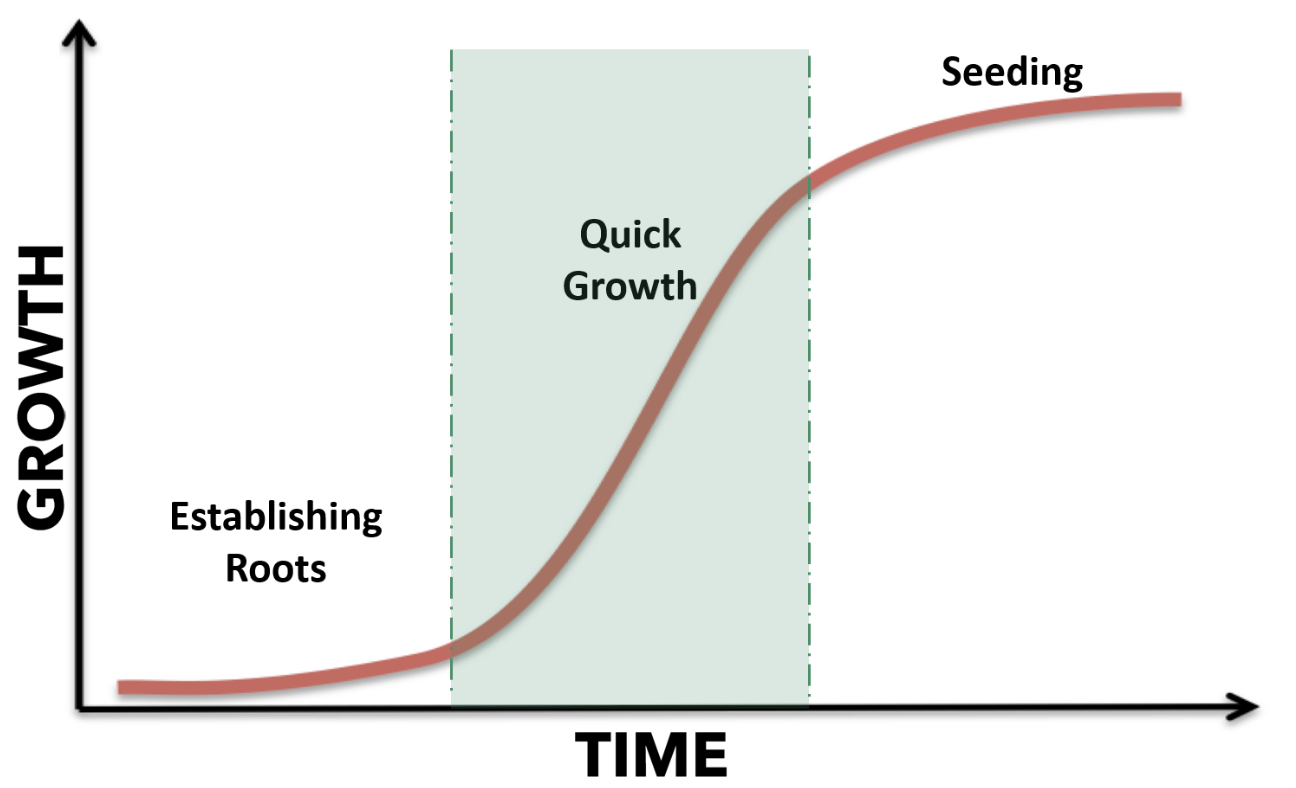

Forage grows in an 'S' curve.

That means that after being sheared, either by a grazing animal or by a mowing machine, it begins growing slowly and then picks up speed before tapering off again as it reaches physiological maturity.

When the plant is sheared, it prunes off roots to focus energy in the crown to send forth new shoots. Pruning takes the pressure off the plant and allows it to put forth new growth and adjust to the shock.

The pruned off grass roots add organic matter to the soil. As the new shoots draw on stored carbohydrates in the crown and roots to send forth new shoots, the plant's energy is temporarily depleted.

The weakened plant returns to energy equilibrium only after the new growth has gotten long enough to capture excess solar energy and regrow root mass. The roots will always mirror the plant's top growth.

We call this "pulsing" the pasture. The idea of letting the plant grow several inches, then shearing it off, and allowing it to regrow to that several-inch level is completely counter to conventional grazing today. In typical grazing, the animals are left on one field for long periods of time and the palatable species are grazed excessively and the unpalatable species are avoided. This constant overgrazing of species and undergrazing of poor ones produces a pasture sward that regresses to fewer and fewer good species while producing more and more poor species like weeds and brush.

Understanding the plant growth cycle is critical to maintaining productive forages. The quick growth part of the 'S' curve is called the "blaze of growth," and it is during this critical time that roots are regrowing and forage volume increases multiplicatively. At the second break point, or the top of the 'S,' the plant's energy reserves are restored; growth slows, and nutrient levels peak.

For optimum forage and livestock performance then, the plants should be consistently harvested at the second 'S' curve break point: right after the blaze of growth and right before the maturity slowdown.

Unfortunately, most forages are harvested at the first break point: right after the slow growth period and before the blaze of growth. Under continuous grazing, palatable forage species are overgrazed while unpalatable ones are undergrazed. A continuously-grazed pasture always looks clumpy. The productivity is greatly affected because by harvesting at the first break point perhaps 20 times per season at a volume of 450 Kg per Hectare per shearing, we have a total of 8,000 pounds of grass harvested per season per acre.

But by allowing the grass to express itself through the blaze of growth and harvesting only 6 times at 3,360 Kg per hectare, the total is 20,200 Kg of forage produced. The only way to achieve optimum productivity is to control when the plants get sheared.

At the same time, animals consistently grazing plants at the first break point will not get the level of nutrition that they should. Such short plants will have short roots, and therefore will not bring up minerals buried lower in the soil. Furthermore, short-rooted plants are more susceptible to drought damage. Weakened plants will not jump back as fast after heat or drought.

This growth cycle cannot be charted on a calendar. It fluctuates with the season and the forage species. Cool season forages grow faster during early spring and late fall. Warm season forages grow faster during the summer. Day length, soil moisture, and ambient temperature all bear on the rapidity of the growth cycle. Sometimes the cycle can occur in 10 days; other times, it may be 50 or in winter, 100 days.

The key is to never allow forages to be re-mowed or re-grazed until energy equilibrium is achieved. This is called "the law of the second bite." A rapidly-growing plant in spring, nipped twice at the first break point, will be weak for the rest of the season. In fact, many plants, especially the palatable ones, actually die due to continual weakening. An animal always eats dessert first. Given a choice between ice cream (clover) and the liver (ragweed) the cow will always choose the ice cream. That is why continuously grazed pastures, over time, tend toward weeds and woody species, and away from clovers and highly succulent grasses. Just as a garden requires careful tending to maintain the desired plants and discourage the undesirables, so a pasture needs careful monitoring so that the shearing cycles will be in sync with the forage growth cycles. Both plants and animals benefit from such control.

Whether it is one goat in a half-acre lot or 1,000 cows on a 10,000-acre ranch, the principle remains the same. The animals should be moved from a grazing area before they have an opportunity to re-graze the new shoots.

All we are trying to do is mimic on a domestic scale what herbivore populations the world over show us. Whether it is Wildebeests on the Serengeti, Caribou in Alaska, Bison on the American range or Reindeer in Lapland, multi-stomached herds are always moving onto fresh ground. They follow forage growth cycles and never stay in one place more than a couple of days. We call that short duration stays.

Secondly, they are always mobbed up. Predators keep them mobbed up. Even though they may have many square miles to graze, they are close together. This mobbing principle we call density. The two D's of grazing: duration and density. High density completely changes the herd's grazing behavior, its interaction with the soil, and its efficiency.

The importance of monitoring the growth cycle and the benefits of doing so are well documented in Allan Savory's Holistic Resource Management and Voisin's Grass Productivity. All I am presenting here is the fundamental concept, nothing more.

Graziering is an art as well as a science. It is like any skill: no one can really do it until they actually do it. As Allan Nation says, it's like driving a car. You can sit in a classroom all day and learn the fine art of driving a car, but until you actually get behind the wheel and take it for a spin, you'll never really know what it's like or how to do it. Experience is definitely the best teacher. After making mistakes, you will begin to get a feel for it and it will become easier and easier. But the only person who can learn it for you is you. It is not a gadget you go out and buy. It is an art form that you mold and create to fit your own piece of ground.

The rewards are myriad. Watching the soil, forage and animals respond through your management rather than through purchased materials and gadgetry is truly fulfilling. I can't imagine why someone would want to go out and till and cultivate and worry about erosion and breathe soil dust when it can be so much greener and more enjoyable.

Graziering is wonderful.